[ad_1]

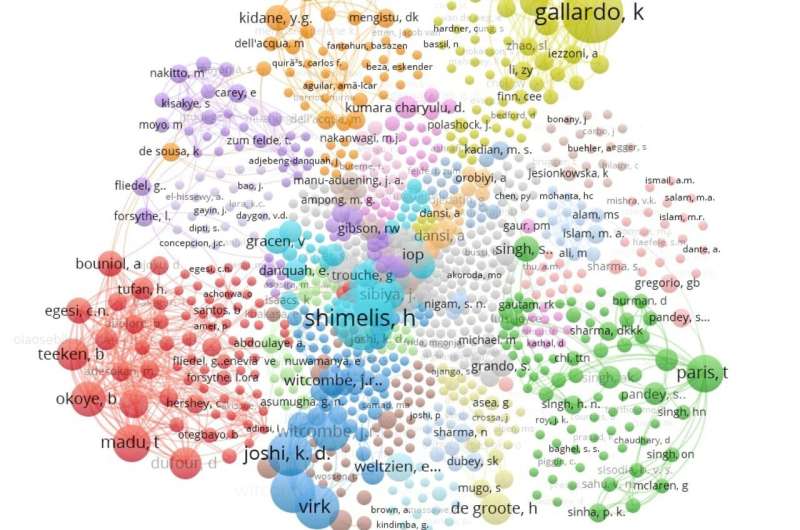

Co-authoring network. The size of the nodes indicates a higher number of collaborations. Edges indicate co-authorship. Nodes are grouped into clusters distinguished by color. anetwork with all authors involved. b, only networks with authors that are part of an edge (i.e. show connections) are included. Credit: Plants of nature (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41477-024-01639-6

A systematic review of 40 years of studies of public crop breeding programs found that grains receive more research attention than crops important to food security, such as fruits and vegetables. Only 33% of studies sought input from both male and female household members. And South America, the Middle East and North Africa have significantly less research than sub-Saharan Africa.

the study, published I Plants of natureIt was authored by Cornell researchers, led by the Priority Setting Team of the Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Crop Improvement (ILCI) and colleagues from the University of Notre Dame and the Center for International Forestry Research and World Agroforestry.

“One question this study asks: What is the cost of getting it wrong?” said Martina O’Kelly, co-head of ILCI’s priority setting team and first author of the paper. “There’s a lot of investment in developing new crop varieties. And if the characteristics of the variety you’re developing don’t match what’s wanted and desired, that’s a waste of time and money.”

When breeders develop new varieties, they seek input from farmers to ensure they are prioritizing the traits most important to the people who grow them, such as which pests are the most problematic, whether high yields or early ripening, and whether farmers have access to irrigation.

However, although only one-third of trait preference studies collected information from male and female household members, when they did collect such data, 84% showed sex-based differences in preferred traits. For example, Sorghum researchers in Mali Those who surveyed both men and women found that women were assigned the least fertile fields to manage. Phosphorus availability was particularly poor on these plots, so breeders specifically selected varieties that could still thrive in phosphorus-deficient fields.

“It’s assumed that men and women have the same farming conditions, but that’s usually not the case,” said Hale Storm, associate professor in the School of Integrative Plant Science (SIPS) Plant Breeding and Genetics Section at CALS. Is.” “In this context, if you develop a variety that is too dependent on phosphorus inputs, you’ve started depriving women. Because of that, women are forced to invest more of their labor and time. will get less because they are growing on the same soil. Unequal.”

The researchers also found that only 12.5% of studies involved farmers in on-farm participatory experiments, in which they test varieties with their own management practices in their own fields.

“In any other field, it would be unthinkable to develop a new technology — that is, a new variety — without Feedback loops from the people who are going to use them,” Storm said. “Participatory research is considered more difficult. It requires more time and engagement with farmers, but it leads to much better data and better adoption rates once the variety is released.”

The uneven geographic distribution of studies also hampers efforts to ensure universality. Food safety, said Occelli, who is also a research associate at SIPS. More than half of all trait preference studies over the past 40 years have been conducted in sub-Saharan Africa. Only 6% of studies were conducted in South America and only 2% in the Middle East and North Africa.

Occelli and Tufan said they hope the work will reach donors, Funding agenciesand international research teams share the need for more equitable research by crop, geographic location, gender, and more.

“This kind of trait preference information requires time and budget, both of which are limited, so we need to be more deliberate when investing in crop breeding programs,” Occelli said.

“We need to correct the imbalance and be fair and thoughtful about why we are privileging certain crops and regions over others,” Storm said. “We hope that bringing attention to these imbalances can lead to change.”

More information:

M. Occelli et al, A scoping review on tools and methods for trait prioritization in crop breeding programs, Plants of nature (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41477-024-01639-6

Provided by

Cornell University

Reference: Inequities in 40 years of crop research (2024, February 22) Retrieved February 22, 2024, from https://phys.org/news/2024-02-years-crop-ineequities.html

This document is subject to copyright. No part may be reproduced without written permission, except for any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research. The content is provided for informational purposes only.

[ad_2]