[ad_1]

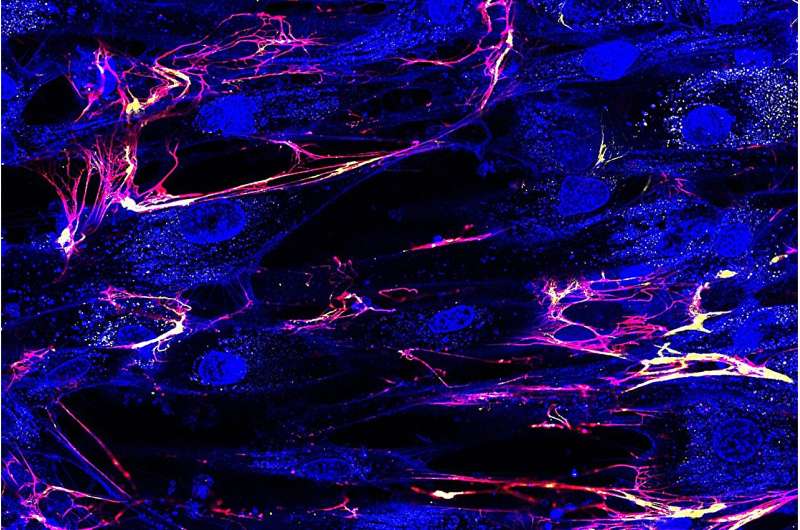

Human corneal cells (shown in blue) form thin filaments of extracellular matrix (yellow collagen and red fibronectin) that form a tissue. Credit: Alexandra Silverman

New research by Northeastern scientists questions the long-held belief that the connective tissues that give us mechanical strength, such as tendons, ligaments, bones and skin, are made up of cells in the human body.

Instead, our tissues are most likely formed by dividing cells. research I was published today Case.

Jeff Roberti, professor of bioengineering at Northeastern University and co-author of the study, says that it has long been believed that human cells use patterns encoded in our DNA to build and assemble tissues. .

“We don’t really understand how small cells are able to interact with molecules much smaller than themselves to coordinate and establish these beautiful, mechanically efficient patterns that we see over time,” he says. become.” “The theory has long been that cells are essentially being assembled individually, or printing tissues, using patterns or algorithms.”

But that’s just a theory, he points out. Roberti and three researchers in his lab have now challenged that, providing evidence that collagen, the main protein that makes up most of our tissues, is preformed and formed by cells. No, our cells are mutually exclusive. one another.

“This material accumulates in the energy pathway, where it reaches a state of low energy but under a high stress load. So, what we propose is that the cells and your body literally Together, they work together to create structure by creating tension lines. That is what collagen turns into. In short, force causes structure, which then resists the force that causes it to bend. causes.”

Roberti conducted the research in his lab with a research scientist, Syed Mohamed Sayadat, Alexandra Silverman, who graduated from Northeastern with a master’s in bioengineering, and Jason Olszewski, a fourth-year bioengineering major.

For the study, the team, using the donation Human cellscreated a model of the human cornea, using advanced microscopes and other measuring and diagnostic equipment to observe the biomechanical processes that occur as the cornea forms. The fact that this process could be observed in real time is because most of the previous studies in this domain relied on images.

“We took cells from a donor’s eye, we put them on a dish, and while they worked to improve The tissuewe observed this process,” says Roberti.

What they observed was that the cells were dividing to form structures, identifying five unique types of stretching.

Roberti’s lab first proposed the phenomenon in 2016, when former Northeastern graduate student Jeff Patton conducted experiments that showed for the first time that if you stretch collagen monomers, they crystallize into structures. will Ruberti predicted that cells could do the same.

The research will be used to help inform treatment processes at Northeastern spinout company BrillantStrings Therapeutics, which he and Patton founded. The discovery could lead to better treatments for fibrosis and others. Medical condition That’s why the wounds don’t heal, says Roberti.

“This opens up a number of possibilities, from sculpting tissues by loading monomers to create structures to treat fibrosis where this process has gone awry,” he added.

“Jeff’s theory seems a little counterintuitive at first because you think cells have a nucleus and this is the cell’s brain,” says Silverman. “Of course they have to know where the collagen is going to go and put it in that way to create the structure. It turns everything on its head and makes you question everything you’ve ever thought.”

In discussing the results, Roberti gets a bit philosophical, noting that there are many ways animals and humans can be literally brought into being.

“You have to stretch to build properly,” he says. “Tension is critical.”

More information:

Alexandra A. Silverman et al., Tension in ranks: cooperative cell contraction drives force-dependent collagen assembly in human fibroblast culture, Case (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.matt.2024.01.023

Provided by

Northeastern University

This story is reprinted courtesy of Northeast Global News. news.northeastern.edu.

Reference: Our ligaments and bones don’t grow the way we thought, new research suggests (2024, Feb 19) February 19, 2024 https://phys.org/news/2024-02-ligaments-bones- Retrieved from dont-thought. html

This document is subject to copyright. No part may be reproduced without written permission, except for any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research. The content is provided for informational purposes only.

[ad_2]